Introduction

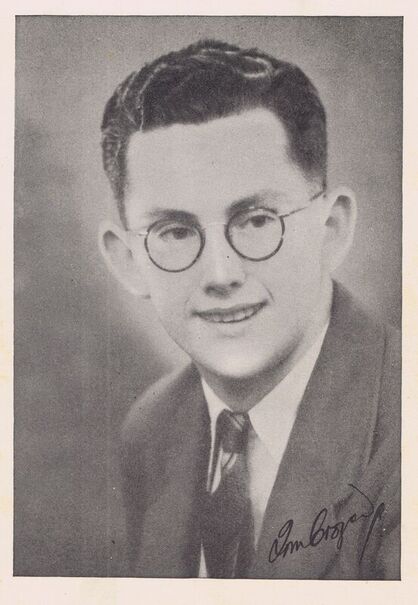

We are extremely fortunate in being able to read about Tom Crozier and his 65 years spent working in Australian Radio.

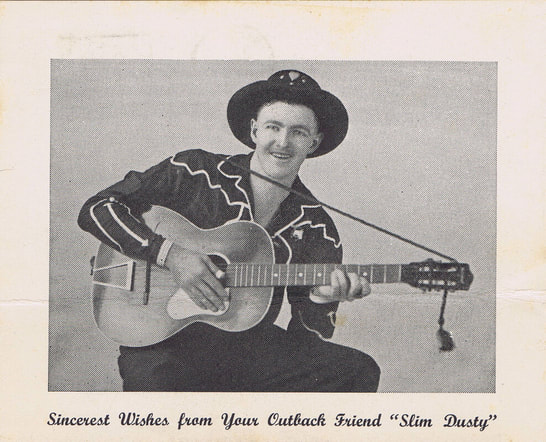

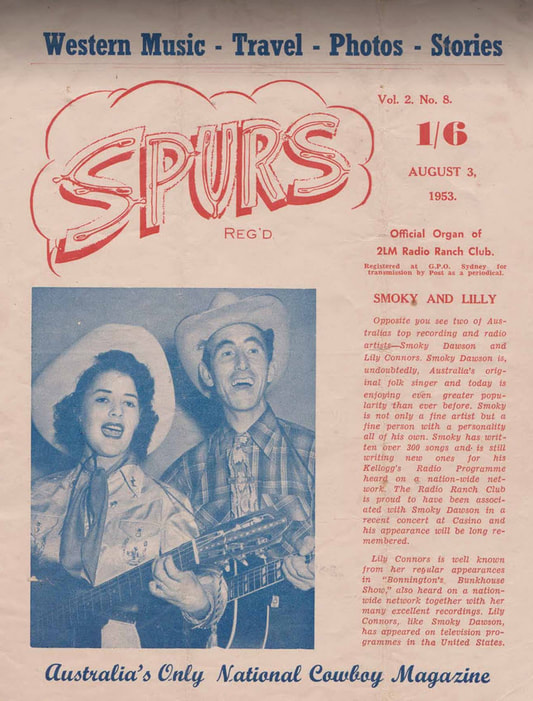

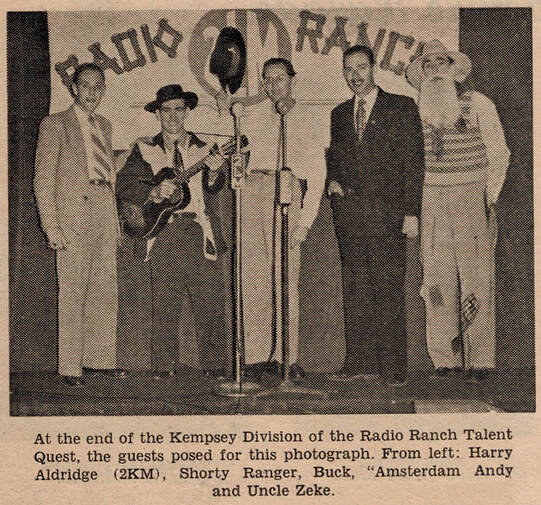

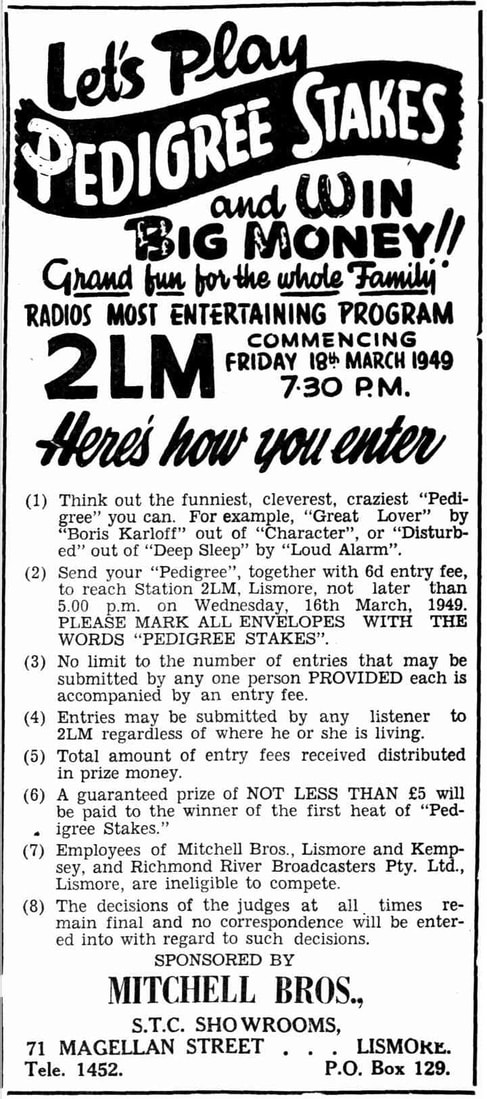

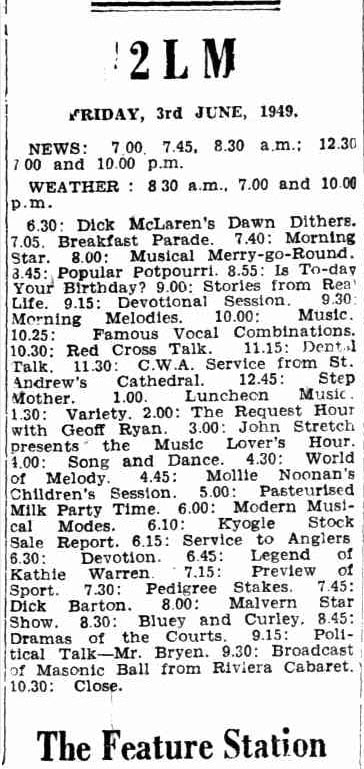

Thanks not only go to Tom Crozier for taking the time to write the following chapters, but also to his family, in particular his daughters Virginia Crozier and Gail Schmierer for sharing them with us. Appropriate photos have been added from various collectors to illustrate the recollections being shared.

A brief timeline:

Born November 1925

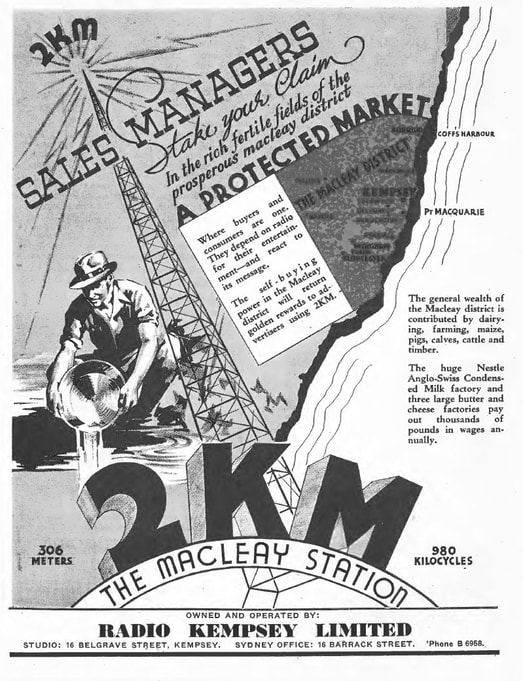

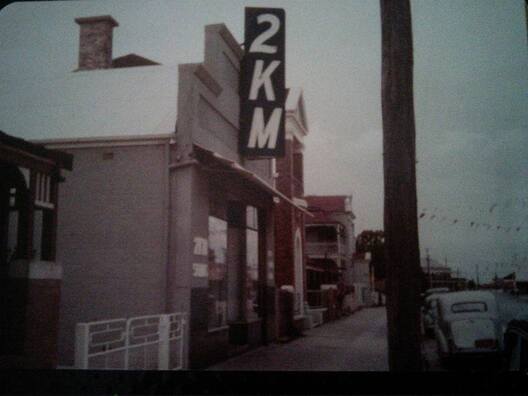

1942 2KM Kempsey

1943 2LT Lithgow

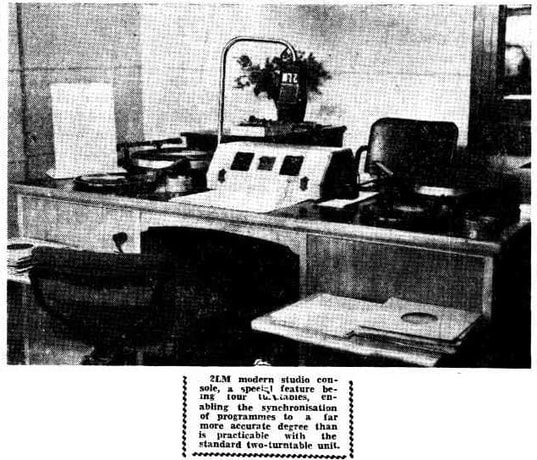

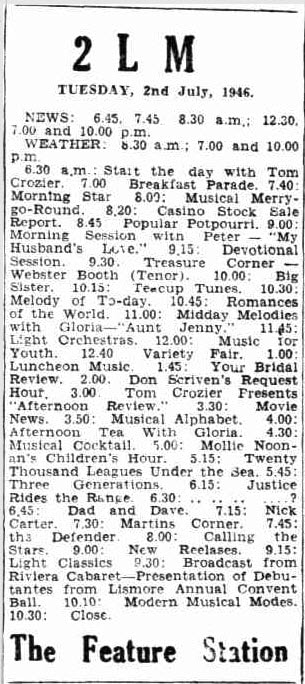

1944-48 2LM Lismore

A brief break where he thought he may pursue a religious calling in the Presbyterian Church

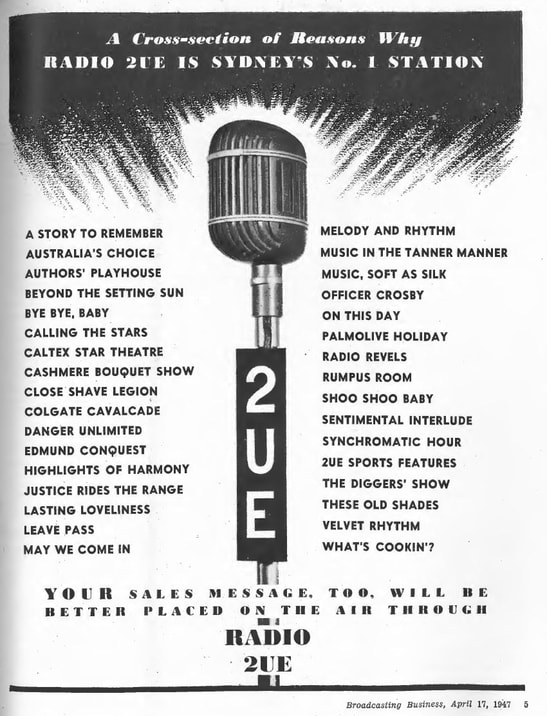

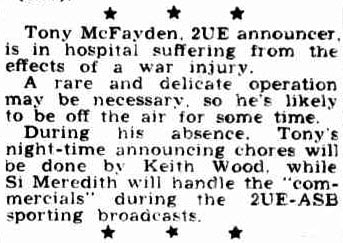

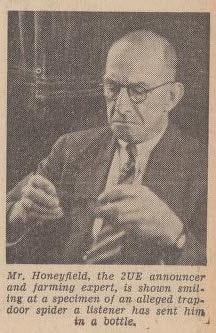

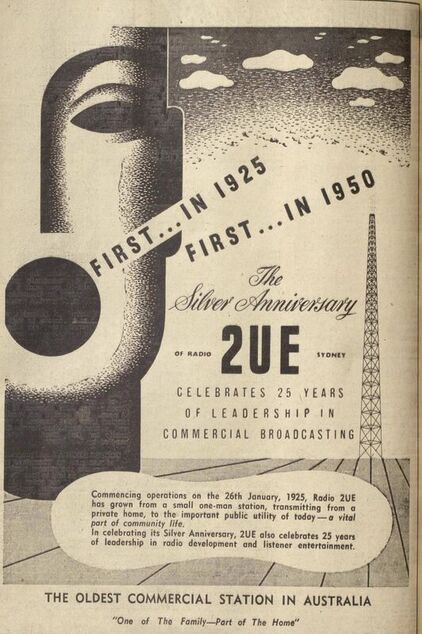

1949-1951 2UE Sydney as an announcer

1951-55 2LM Lismore again

1955-61 2WL Wollongong

1961-81 2UE, initially as announcer then salesman, 1968-1977 as Sales Manager, then group manager of affiliate stations (KA, MC)

1981-89 Marketing Director, Radio Marketing Bureau

1990-91 helped in setting up community station in Sutherland Shire

1992-2003 Manager, Radio 2RPH (Radio for Print Handicapped)

Thomas Francis Roy Crozier died 13th September 2010, aged 84

Thanks not only go to Tom Crozier for taking the time to write the following chapters, but also to his family, in particular his daughters Virginia Crozier and Gail Schmierer for sharing them with us. Appropriate photos have been added from various collectors to illustrate the recollections being shared.

A brief timeline:

Born November 1925

1942 2KM Kempsey

1943 2LT Lithgow

1944-48 2LM Lismore

A brief break where he thought he may pursue a religious calling in the Presbyterian Church

1949-1951 2UE Sydney as an announcer

1951-55 2LM Lismore again

1955-61 2WL Wollongong

1961-81 2UE, initially as announcer then salesman, 1968-1977 as Sales Manager, then group manager of affiliate stations (KA, MC)

1981-89 Marketing Director, Radio Marketing Bureau

1990-91 helped in setting up community station in Sutherland Shire

1992-2003 Manager, Radio 2RPH (Radio for Print Handicapped)

Thomas Francis Roy Crozier died 13th September 2010, aged 84

Working on the Wireless - Memories of a Life spent in Radio - TOM CROZIER

Here is the News - 1925-2000

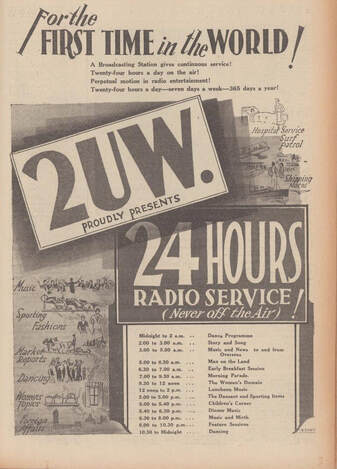

2UE, 5DN, 3UZ and 2KY begin broadcasting in 1925, the year I was born;

Sydney's first section of underground railway opens, 1926;

Mr Traegar's pedal wireless is developed for Flynn's proposed flying doctor service and Canberra's Federal Parliament opens, 1927;

Pedal wireless gets its workout as flying doctor takes to the air; Kingsford Smith succeeds in flight from America to Australia, 1928;

First airmail stamps issued; 3L0 Melbourne begins with kookaburra as signature, 1929;

First wireless telephone contact with England, 1930;

Jack Davey arrives in Australia to take it by storm, 1931;

Sydney Harbour Bridge opens; ABC established; Aeroplane Jelly song is composed, 1932;

Bodyline bowling "just not cricket"; Kingsford Smith breaks England-Australia air flight record, 1933;

Tivoli comedian Roy Rene (Mo) a flop in movies, 1934;

Qantas first international flight to Singapore: Kingsford Smith is lost in Bay of Bengal, Cane Toad introduced in Queensland, Tarzan's Grip launched, 1935;

Edward V111 quits, Hume Dam is commissioned: 1936:

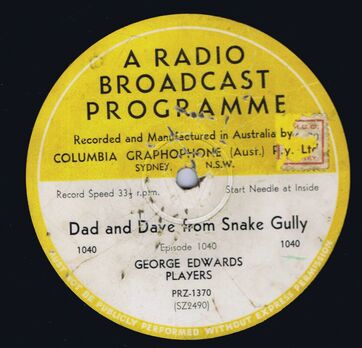

Dad and Dave the radio serial starts on 2UW, first Australia-US airmail, 1937;

Qantas international flights extended to England - flight time 10 days; Prime Minister Robert Menzies

dubbed "Pig Iron Bob" by wharf workers; population reaches 6,936,000, 1938;

World War 2 begins, 1939;

Petrol rationing starts; newsprint rationed, papers smaller; 1940;

Banjo Patterson dies, Tobruk relieved HMAS Sydney lost Australia's Prime Minister John Curtin "looks to the United States", 1941;

Daylight Saving introduced (wartime measure only!); Japanese forces in New Guinea; Japanese midget subs in Sydney Harbour; General Douglas MacArthur arrives in Australia; ration books issued; Australian radio stations transmitting from 6.30am to midnight only; I get my first job in radio. 1942;

Federal Government grants franchise to certain aboriginals (those entitled to vote in their own state, members or ex-members of armed forces); Australian Broadcasting Control Board appointed; petrol rationing ends; Snowy Mountains Scheme starts; Menzies becomes Prime Minister, I move to 2UE Sydney 1949;

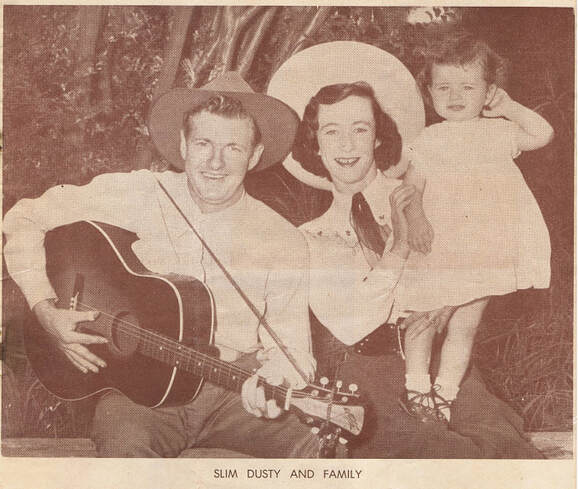

I marry Nancy Begg and return to Lismore 1951.

We move to 2WL Wollongong (now WAVE FM) 1955.

Back to Sydney and 2UE for 20 years, 1961.

Director Radio Marketing Bureau - part of Federation of Australian Broadcasters (now Commercial Radio Australia) 1981

Retire 1989.

Consultancy 1989 - 1992.

Involved in Community Radio (especially 2RPH) 1992 - 2003.

Fully retired, if not really pleased about it - September 2003

2UE, 5DN, 3UZ and 2KY begin broadcasting in 1925, the year I was born;

Sydney's first section of underground railway opens, 1926;

Mr Traegar's pedal wireless is developed for Flynn's proposed flying doctor service and Canberra's Federal Parliament opens, 1927;

Pedal wireless gets its workout as flying doctor takes to the air; Kingsford Smith succeeds in flight from America to Australia, 1928;

First airmail stamps issued; 3L0 Melbourne begins with kookaburra as signature, 1929;

First wireless telephone contact with England, 1930;

Jack Davey arrives in Australia to take it by storm, 1931;

Sydney Harbour Bridge opens; ABC established; Aeroplane Jelly song is composed, 1932;

Bodyline bowling "just not cricket"; Kingsford Smith breaks England-Australia air flight record, 1933;

Tivoli comedian Roy Rene (Mo) a flop in movies, 1934;

Qantas first international flight to Singapore: Kingsford Smith is lost in Bay of Bengal, Cane Toad introduced in Queensland, Tarzan's Grip launched, 1935;

Edward V111 quits, Hume Dam is commissioned: 1936:

Dad and Dave the radio serial starts on 2UW, first Australia-US airmail, 1937;

Qantas international flights extended to England - flight time 10 days; Prime Minister Robert Menzies

dubbed "Pig Iron Bob" by wharf workers; population reaches 6,936,000, 1938;

World War 2 begins, 1939;

Petrol rationing starts; newsprint rationed, papers smaller; 1940;

Banjo Patterson dies, Tobruk relieved HMAS Sydney lost Australia's Prime Minister John Curtin "looks to the United States", 1941;

Daylight Saving introduced (wartime measure only!); Japanese forces in New Guinea; Japanese midget subs in Sydney Harbour; General Douglas MacArthur arrives in Australia; ration books issued; Australian radio stations transmitting from 6.30am to midnight only; I get my first job in radio. 1942;

Federal Government grants franchise to certain aboriginals (those entitled to vote in their own state, members or ex-members of armed forces); Australian Broadcasting Control Board appointed; petrol rationing ends; Snowy Mountains Scheme starts; Menzies becomes Prime Minister, I move to 2UE Sydney 1949;

I marry Nancy Begg and return to Lismore 1951.

We move to 2WL Wollongong (now WAVE FM) 1955.

Back to Sydney and 2UE for 20 years, 1961.

Director Radio Marketing Bureau - part of Federation of Australian Broadcasters (now Commercial Radio Australia) 1981

Retire 1989.

Consultancy 1989 - 1992.

Involved in Community Radio (especially 2RPH) 1992 - 2003.

Fully retired, if not really pleased about it - September 2003

Chapter One

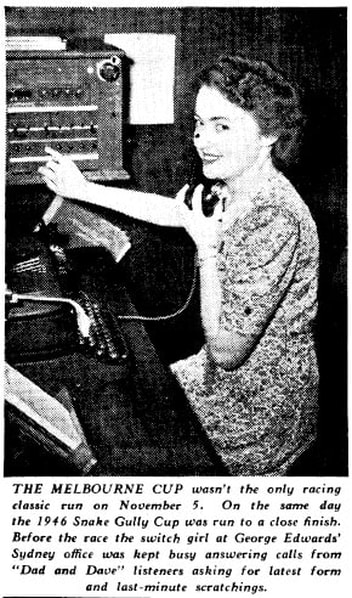

Commercial Broadcasting - November 1946

Commercial Broadcasting - November 1946

PHIL CHARLEY stood up to speak.

"I have here a short piece, written by Tom's sister..." he said.

Up until that time Phil and I had been good friends for forty years, just about. I figured that we would have to stay friends even after what would have to be a momentous intrusion into my past, for there would have had to have been three others involved in having this document read today. One was my colleague, Bob Logie, who'd organised this traditional gathering of radio friends and enemies on the occasion of my "retirement", the second would have been one of my daughters, Virginia, who knows about the skeletons and even the cupboards they're in, and the writer herself, Mary. And I wanted to stay friends with all of them.

Mary wrote a short story of a radio station I had invented. It was called 2WF, after Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains of NSW, because almost all radio stations were named in that way then. They took a couple of letters from the country town they served, added a "2","3","4" to represent their home state (based on old military planning zones but adopted by the states) and that was it.

My microphones were made from dad's empty Log Cabin tobacco tins, which I would liberally sprinkle with holes using a tin opener. The holes were necessary to let the sound in, of course.

These microphones were mounted in a disused fowl house at the end of our yard, where it was quiet because the bush came right up to our boundary. Radio programs originated from there whenever I wasn't at primary school. 2WF didn't have a transmitter because I wasn't aware that such a thing was needed.

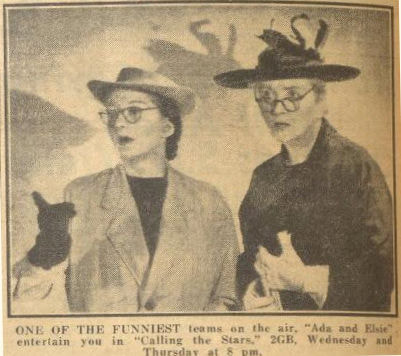

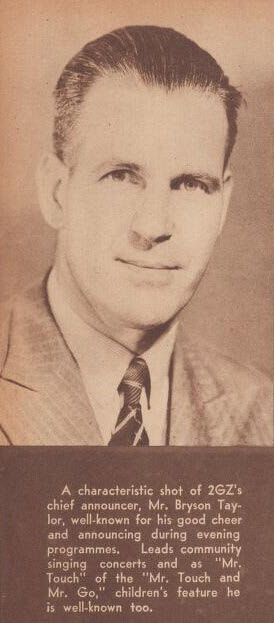

Community singing was in vogue (it was the time of the Great Depression and cheap entertainment was the go). We had been to the Sydney Town Hall for a broadcast of the community singing concert one lunch-time, so I knew what was needed, having studied the conductorship of one Bryson Taylor who was a star of 2BL.

To have community singing, you had to have an audience. So Mary became that audience. Admittedly an audience of one was quite small, but one had to make do. The stage was the roof of the fowl house.

Community singing done, the conductor would jump to the ground and enter the studio to continue with a musical program, as the audience made its way round to the front gate and eventually back through the vegetable garden to the studio.

I was probably seven or eight.

The radio game was inspired by the first family radio, bought in 1932. It was an Airzone - marketed with the lines "fine Radio" and "Airzone's tone is Airzone's own". It came on the "never never" from the local grocery and hardware store, and the delivery man, Mr. Duncan, installed it for us by dint of hooking a piece of "aerial wire" to a nearby gum tree and switching the power on.

It was a cabinet model (who had even thought of a mantel radio in 1932 - personal portables were twenty five years into the future) and stood next to the fireplace in the "dining room" of our Blue Mountains home. But it could be heard quite easily as we ate our meals in the kitchen, where we always dined, the dining room itself being kept clean and tidy for the benefit of rare visitors.

You could hear programs from everywhere - a boys club concert from South Australia - a variety show from Melbourne - an old time dance from Sydney - and later, I could hear seven different episodes of "Yes, What?", a schoolroom farce, from seven different far-away locations at seven different times. And all on the same night.

This particular radio both fascinated and scared the hell out of me.

The trouble was that our set had been born with a microphonic valve. At least, I think that was the problem. Maybe it had others, but of course in its day it was what would become known in the business as a FRED - a flamin' ridiculous electronic device.

It would start off playing sweet and low, spreading its magic all through the house. Then it would emit a piercing shriek that turned my blood cold. Having achieved that, it continued to shriek until someone did something about it. That sound would send me racing out of the house, day or night - not to be coaxed back until it had stopped, either of its own accord, or by depriving it of its life force - the electric power we'd had installed some weeks before.

My mother had a cure for this terrible illness, as indeed she had a cure for everything else. The cure came in a blue glass jar and was called Vaseline. She conceived the idea that the problem was with the plug, and therefore, quite logically, dipped the plug into the Vaseline, then plugged it back in and switched the wireless back on. When this failed, as it did every time, she began to plaster the universal remedy liberally around the plug as it sat in its socket. Why nobody got electrocuted still remains one of life's deep and abiding mysteries.

There came the time when, with Vaseline dripping from the power point, the radio squealing and shrieking (now with added high pitched whistling) that the grandfather walked into the house one Sunday as we persevered with an attempt to hear the Aeroplane Jelly song from the comfort of the kitchen.

The first we knew about his arrival is that the radio stopped, then he strode into the kitchen with the words "That's enough of THAT!" He continued to have scant desire to listen to the radio for the rest of his life. Whenever he came to visit, the radio was switched off for the duration.

The faulty valve was repaired just in time for us to hear about the start of World War 2, by which time I had convinced my mother that we should have one of the new mantel radios. This one was better than the first one. It made no distressing noises, except those deliberately transmitted from the commercial stations (to which my mother had a strong and oft-repeated aversion), and it picked up the short-wave! I could hear the English broadcasts from Japan and the propaganda about the "greater South East Asia co-prosperity sphere". often read by an Australian prisoner of war.

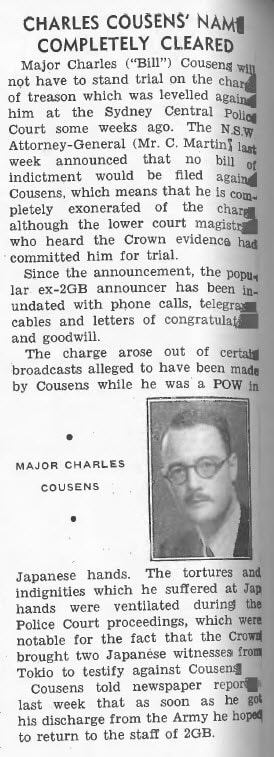

That POW was Charles Cousins, whose pre-war "Radio Reporters" program on 2GB had kept me glued to the receiver at 6 o'clock on winter nights, speaking from so far away, and in such stilted tones. He later told the authorities he had helped to train the Japanese English-language broadcasters by placing an undue emphasis on controlling one's breathing. This had the absolutely predictable result that they couldn't control their breathing properly - so they would stop to take a breath at all the wrong places.

Even before that - by the time I was ten - I had decided that I was going to work "on the wireless".

It wasn't a popular choice. My mother wanted me to work in a bank. My father was nonplussed about radio, although he was a fan of "Dad and Dave", but wisely took the view that life would be easier if he pushed the bank line too.

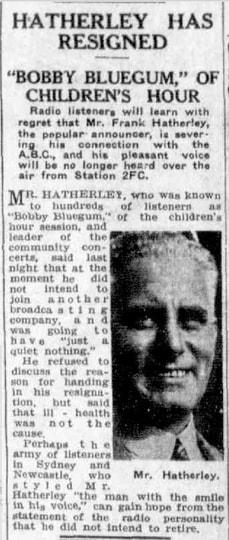

If there is anyone to blame for my choice of a career, it is Bobby Bluegum. Bobby ran the children's session on 2FC at 5.30 each afternoon. He'd taken the words of an English broadcaster as his opening gambit - each afternoon after the chimes from the GPO clock, he would mellow the airwaves with "Hello ...hello...hello ..." and there'd be music, and radio plays, and birthday calls in which the lucky birthday girls and boys were advised to "follow the string from the back of the wireless" to find their present.

My mother heard that children could go to the studio and sit and watch, so one day the three of us, she, Mary and I, took the train to the city where she shopped, as usual, at Marcus Clarks, in Central Square.

Marcus Clarks used a rising sun logo with the words "Bound to Rise", but eventually the company set.

At that store, mum could put any purchase on the account and still pay it all off at five bob a week.

The shopping done by the end of the day, all the trio had to do was to catch the tram down to Market Street where 2FC was.

"I have here a short piece, written by Tom's sister..." he said.

Up until that time Phil and I had been good friends for forty years, just about. I figured that we would have to stay friends even after what would have to be a momentous intrusion into my past, for there would have had to have been three others involved in having this document read today. One was my colleague, Bob Logie, who'd organised this traditional gathering of radio friends and enemies on the occasion of my "retirement", the second would have been one of my daughters, Virginia, who knows about the skeletons and even the cupboards they're in, and the writer herself, Mary. And I wanted to stay friends with all of them.

Mary wrote a short story of a radio station I had invented. It was called 2WF, after Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains of NSW, because almost all radio stations were named in that way then. They took a couple of letters from the country town they served, added a "2","3","4" to represent their home state (based on old military planning zones but adopted by the states) and that was it.

My microphones were made from dad's empty Log Cabin tobacco tins, which I would liberally sprinkle with holes using a tin opener. The holes were necessary to let the sound in, of course.

These microphones were mounted in a disused fowl house at the end of our yard, where it was quiet because the bush came right up to our boundary. Radio programs originated from there whenever I wasn't at primary school. 2WF didn't have a transmitter because I wasn't aware that such a thing was needed.

Community singing was in vogue (it was the time of the Great Depression and cheap entertainment was the go). We had been to the Sydney Town Hall for a broadcast of the community singing concert one lunch-time, so I knew what was needed, having studied the conductorship of one Bryson Taylor who was a star of 2BL.

To have community singing, you had to have an audience. So Mary became that audience. Admittedly an audience of one was quite small, but one had to make do. The stage was the roof of the fowl house.

Community singing done, the conductor would jump to the ground and enter the studio to continue with a musical program, as the audience made its way round to the front gate and eventually back through the vegetable garden to the studio.

I was probably seven or eight.

The radio game was inspired by the first family radio, bought in 1932. It was an Airzone - marketed with the lines "fine Radio" and "Airzone's tone is Airzone's own". It came on the "never never" from the local grocery and hardware store, and the delivery man, Mr. Duncan, installed it for us by dint of hooking a piece of "aerial wire" to a nearby gum tree and switching the power on.

It was a cabinet model (who had even thought of a mantel radio in 1932 - personal portables were twenty five years into the future) and stood next to the fireplace in the "dining room" of our Blue Mountains home. But it could be heard quite easily as we ate our meals in the kitchen, where we always dined, the dining room itself being kept clean and tidy for the benefit of rare visitors.

You could hear programs from everywhere - a boys club concert from South Australia - a variety show from Melbourne - an old time dance from Sydney - and later, I could hear seven different episodes of "Yes, What?", a schoolroom farce, from seven different far-away locations at seven different times. And all on the same night.

This particular radio both fascinated and scared the hell out of me.

The trouble was that our set had been born with a microphonic valve. At least, I think that was the problem. Maybe it had others, but of course in its day it was what would become known in the business as a FRED - a flamin' ridiculous electronic device.

It would start off playing sweet and low, spreading its magic all through the house. Then it would emit a piercing shriek that turned my blood cold. Having achieved that, it continued to shriek until someone did something about it. That sound would send me racing out of the house, day or night - not to be coaxed back until it had stopped, either of its own accord, or by depriving it of its life force - the electric power we'd had installed some weeks before.

My mother had a cure for this terrible illness, as indeed she had a cure for everything else. The cure came in a blue glass jar and was called Vaseline. She conceived the idea that the problem was with the plug, and therefore, quite logically, dipped the plug into the Vaseline, then plugged it back in and switched the wireless back on. When this failed, as it did every time, she began to plaster the universal remedy liberally around the plug as it sat in its socket. Why nobody got electrocuted still remains one of life's deep and abiding mysteries.

There came the time when, with Vaseline dripping from the power point, the radio squealing and shrieking (now with added high pitched whistling) that the grandfather walked into the house one Sunday as we persevered with an attempt to hear the Aeroplane Jelly song from the comfort of the kitchen.

The first we knew about his arrival is that the radio stopped, then he strode into the kitchen with the words "That's enough of THAT!" He continued to have scant desire to listen to the radio for the rest of his life. Whenever he came to visit, the radio was switched off for the duration.

The faulty valve was repaired just in time for us to hear about the start of World War 2, by which time I had convinced my mother that we should have one of the new mantel radios. This one was better than the first one. It made no distressing noises, except those deliberately transmitted from the commercial stations (to which my mother had a strong and oft-repeated aversion), and it picked up the short-wave! I could hear the English broadcasts from Japan and the propaganda about the "greater South East Asia co-prosperity sphere". often read by an Australian prisoner of war.

That POW was Charles Cousins, whose pre-war "Radio Reporters" program on 2GB had kept me glued to the receiver at 6 o'clock on winter nights, speaking from so far away, and in such stilted tones. He later told the authorities he had helped to train the Japanese English-language broadcasters by placing an undue emphasis on controlling one's breathing. This had the absolutely predictable result that they couldn't control their breathing properly - so they would stop to take a breath at all the wrong places.

Even before that - by the time I was ten - I had decided that I was going to work "on the wireless".

It wasn't a popular choice. My mother wanted me to work in a bank. My father was nonplussed about radio, although he was a fan of "Dad and Dave", but wisely took the view that life would be easier if he pushed the bank line too.

If there is anyone to blame for my choice of a career, it is Bobby Bluegum. Bobby ran the children's session on 2FC at 5.30 each afternoon. He'd taken the words of an English broadcaster as his opening gambit - each afternoon after the chimes from the GPO clock, he would mellow the airwaves with "Hello ...hello...hello ..." and there'd be music, and radio plays, and birthday calls in which the lucky birthday girls and boys were advised to "follow the string from the back of the wireless" to find their present.

My mother heard that children could go to the studio and sit and watch, so one day the three of us, she, Mary and I, took the train to the city where she shopped, as usual, at Marcus Clarks, in Central Square.

Marcus Clarks used a rising sun logo with the words "Bound to Rise", but eventually the company set.

At that store, mum could put any purchase on the account and still pay it all off at five bob a week.

The shopping done by the end of the day, all the trio had to do was to catch the tram down to Market Street where 2FC was.

1935 - Labor Daily

1935 - Labor Daily

There was a silver-haired fellow waiting at the lift and as we went in he greeted us with three hellos, and I knew it was HIM.

I was not at all surprised that he should meet us at the lift and take us up to the studio level, but I was disappointed to some degree because he was just an ordinary person. But there was compensation in the fact that he did have the air of a slightly bemused koala bear.

I was right, of course. Bobby Bluegum not only prepared the session and presented it, he completed the trifecta by driving a lift full of scruffy kids up to the studio so they could watch it. That was certainly doing everything!

But tragedy struck.

Suddenly, Bobby was missing from the children's session - and from the community singing concerts he also compered on 2BL.

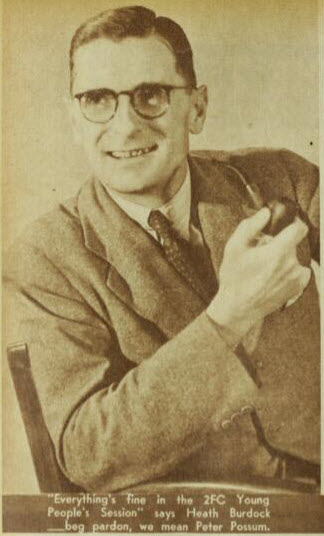

I was lost. I was so disconsolate that my mum wrote to Peter Possum (Peter had taken over from Bobby) and he had replied - remarkably for a possum, in his own hand - that Bobby would doubtless bob up one day. He did, of course, but somewhere along the way he had changed his name to Frank Hatherley.

Years later, I almost knocked Bobby over in the crowded foyer of the State Shopping Block. He was working at 2UW, which was somewhere upstairs. I felt the need to tell him that he had inspired me to go into radio, but I didn't know how to address him. Was it "Bobby", or "Mr. Hatherley" or "Frank"? It was too hard and a mite embarrassing. I let the opportunity pass.

I'm sure, if he had guessed, he would have been glad nothing was said. After all, he might have said "that's too bad, son".

THE AEROPLANE JELLY SONG:

"I like Aeroplane Jelly

Aeroplane Jelly for me

I like it for dinner

I like it for tea

A little each day is

a good remedy...

The quality's high as the name would imply

And it's made from pure fruit that's one good reason why

I like Aeroplane Jelly

Aeroplane Jelly for me...

It came in waltz time, jazz and whatever, and rumour had it that the orchestra was the ABC Dance Band moonlighting. The singer was a small girl named Joy Adamson.

I was not at all surprised that he should meet us at the lift and take us up to the studio level, but I was disappointed to some degree because he was just an ordinary person. But there was compensation in the fact that he did have the air of a slightly bemused koala bear.

I was right, of course. Bobby Bluegum not only prepared the session and presented it, he completed the trifecta by driving a lift full of scruffy kids up to the studio so they could watch it. That was certainly doing everything!

But tragedy struck.

Suddenly, Bobby was missing from the children's session - and from the community singing concerts he also compered on 2BL.

I was lost. I was so disconsolate that my mum wrote to Peter Possum (Peter had taken over from Bobby) and he had replied - remarkably for a possum, in his own hand - that Bobby would doubtless bob up one day. He did, of course, but somewhere along the way he had changed his name to Frank Hatherley.

Years later, I almost knocked Bobby over in the crowded foyer of the State Shopping Block. He was working at 2UW, which was somewhere upstairs. I felt the need to tell him that he had inspired me to go into radio, but I didn't know how to address him. Was it "Bobby", or "Mr. Hatherley" or "Frank"? It was too hard and a mite embarrassing. I let the opportunity pass.

I'm sure, if he had guessed, he would have been glad nothing was said. After all, he might have said "that's too bad, son".

THE AEROPLANE JELLY SONG:

"I like Aeroplane Jelly

Aeroplane Jelly for me

I like it for dinner

I like it for tea

A little each day is

a good remedy...

The quality's high as the name would imply

And it's made from pure fruit that's one good reason why

I like Aeroplane Jelly

Aeroplane Jelly for me...

It came in waltz time, jazz and whatever, and rumour had it that the orchestra was the ABC Dance Band moonlighting. The singer was a small girl named Joy Adamson.

Chapter Two

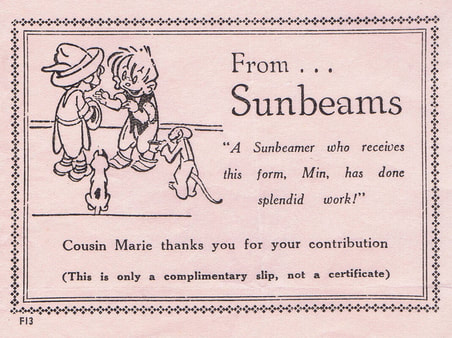

Sunbeams Complimentary Slip from Cousin Marie - Ian Grieve Collection

Sunbeams Complimentary Slip from Cousin Marie - Ian Grieve Collection

PHIL was on to short stories now.

When Phil and I first met, at 2LM Lismore, I used to write stories in the copy department on Saturday afternoons. It was a way of filling in time before the severely rationed pubs would open around 5 o'clock (and close at 6). Phil and another mate, Dick McLaren would often come in and wait around for the same event. But Phil didn't know how my writing career began.

"Sunbeams" was the comic section in the old Sun Herald when I was at school, and it had always been my ambition to get something published in it. That didn't mean I was losing interest in the wireless - just that this was something I could do NOW, while I was just getting into my teens. Radio would have to wait until school was finished.

I first tried my hand at writing short, descriptive pieces. It must have had something to do with whatever the English teacher was pushing down our throats at Katoomba High School. These pieces were eminently unsuccessful, although no rejection slips were ever issued by Cousin Marie, who ran the editorial section. (I met her at 2UE ten years later and she didn't look at all like the line drawing of her in Sunbeams. Somehow she wasn't the slim young thing I thought she was - maybe the artist had drawn her as a child). You knew you were accepted, and that 5/- or 10/6 would be in the mail if you opened the comic on Sunday and saw your effort in print. The amount you got seemed to be directly related to the size of the piece.

The first one to make it was indeed a description, written in ten minutes in the school playground minutes after I'd noticed a bed of cloud lying in the valley below as the school train sped between Leura and Katoomba. I had never noticed before how soft and still the cloud looked, and somehow the words came easily.

When Phil and I first met, at 2LM Lismore, I used to write stories in the copy department on Saturday afternoons. It was a way of filling in time before the severely rationed pubs would open around 5 o'clock (and close at 6). Phil and another mate, Dick McLaren would often come in and wait around for the same event. But Phil didn't know how my writing career began.

"Sunbeams" was the comic section in the old Sun Herald when I was at school, and it had always been my ambition to get something published in it. That didn't mean I was losing interest in the wireless - just that this was something I could do NOW, while I was just getting into my teens. Radio would have to wait until school was finished.

I first tried my hand at writing short, descriptive pieces. It must have had something to do with whatever the English teacher was pushing down our throats at Katoomba High School. These pieces were eminently unsuccessful, although no rejection slips were ever issued by Cousin Marie, who ran the editorial section. (I met her at 2UE ten years later and she didn't look at all like the line drawing of her in Sunbeams. Somehow she wasn't the slim young thing I thought she was - maybe the artist had drawn her as a child). You knew you were accepted, and that 5/- or 10/6 would be in the mail if you opened the comic on Sunday and saw your effort in print. The amount you got seemed to be directly related to the size of the piece.

The first one to make it was indeed a description, written in ten minutes in the school playground minutes after I'd noticed a bed of cloud lying in the valley below as the school train sped between Leura and Katoomba. I had never noticed before how soft and still the cloud looked, and somehow the words came easily.

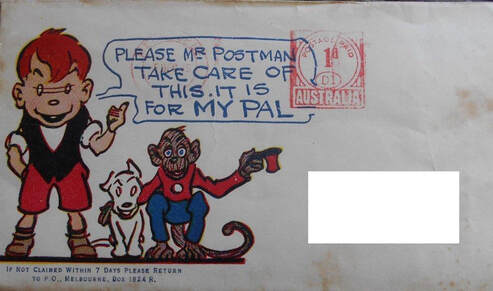

Sunbeams Envelope - Ian Grieve Collection

Sunbeams Envelope - Ian Grieve Collection

When the 5/- arrived in an envelope with a drawing of Ginger Meggs on the front, with Ginger saying "Please Mr Postman - take care of this - it's for my friend Tom Crozier..." I was overcome by emotion and greed for more - I thought I was on my way.

Now for stories, I thought.

I had received book of short stories at the primary school as a prize the year I left - 1938. I picked it up again - and I was suddenly lifted into a new world - mainly the incredible world of Steven Leacock, whose "Soaked in Seaweed" I could once recite almost in its entirety from memory.

This, I thought, was the kind of stuff I would like to write. It was just good fun. I had a go. I wrote three hundred words of nonsense.

Three weeks later, it was published. Not only that, but it was in the prime position where the prize was 10/6, the same price as the Mad Hatter's Hat in Alice in Wonderland..

Sure, Cousin Marie had changed the title, cut it down to Sunbeams size, and she'd changed the last line (the original probably being very much a school yard idea of humour, but I liked it better). No matter. It was there. It had my name on it, although I now wrote under the name Thomas, rather than Tom. I had decided that Thomas looked better for a writer.

There followed several of these, all credited to me and each one showing a slightly different address. The name of the house seemed to change with each publication. Did we move from house to house in Wood Street? Hardly possible. There was only one house there. This cries out for an explanation.

The reason was simple. My mother had become sick and tired of being poor. She had taken up the sciences of astrology and numerology and with her usual enthusiasm for a project, had put what little knowledge she gained into determined full-time practice.

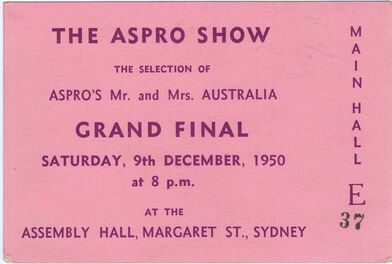

It was my fault, of course. In 1936 or thereabouts, someone had handed me a copy of the Aspro Year Book on the way home from school. This eminent publication, now sadly gone, was an annual full of information about what the stars said must inevitably happen during the following year, the benefits of numerology, how to plant by the stars, horoscopes of the famous, and a million conflicting slogans for the product it was named for, none of which would get past today's health watchdogs.

First came numerology, where you added up any number that was more than one digit long and kept adding the result together until you got a single number. Then you could tell whether your number was "fortunate". If you wanted to check out your name in numerology, it was also simple: every letter of the alphabet had a number. You added all the numbers up.

Mum changed the name of the house in quick succession from Thornton to Allambie to Alanbie and so many others that sometimes I had to check on the house name, just in case I'd missed something. Each one, of course, was more likely to produce wealth and success and happiness than its predecessor, but always failing in some mysterious way.

Then to the stars. This became a serious business, especially since she could hear at least two experts on the subject on radio. (It was commercial radio, which she had no time for, but at least it was on two of the "better" ones, 2GB and 2UW). 2GB had a gentleman from a library which specialised in Theosophical topics. The Theosophical Society owned the 2GB licence. This library had a stack of books on astrology, many of them written half a century before. The other guru was an Egyptian gentleman who apparently materialised in the 2UW studio in full traditional garb two or three times a week. But it encouraged mum to study the art of telling her future by the stars.

So our trips to Sydney now ended up, not in the studios watching a children's session, but at the Library in the basement of 29 Bligh Street - an address I was to get to know and love many years later. At the time the building also contained 2GB and 2UE.

The way to win the lottery, according to the way my mother read the astrology books, was to buy a ticket at the time when the stars were exactly right. She would look for a propitious sign - like the conjunction of Jupiter and Venus, for example. If it were to occur at 9.37 Australian Eastern Standard Time, she would take the early morning train to Sydney, ride the tram down Castlereagh Street to Barrack Street, then walk up to the Lottery Office. There she would stand on the steps until about fifteen minutes before the appointed time and before joining a queue.

There would be a great deal of shuffling and dodging, as she realised that she would get to the head of the line before the selected time. The strategy then was to turn to the person behind her and offer to change places. This working back process might happen two or three times before she got it just right - even then she lived in dread of the person ahead of her ordering several tickets at the same time to the ruination of her scientific plan..

When she got to the counter, if there were just a few seconds to wait, she would fiddle with the papers until the very instant of the conjunction, and triumphantly purchase her Ticket to Freedom.

Sadly, it never happened. I privately formed the opinion that she was not taking into account the enormous time difference between Earth and Venus.

She would have loved the no-nonsense method of buying a lottery ticket today.

The best thing that ever did occur was when mum spotted a ten pound note in the gutter as she was riding her bike. (She had bought one in her early forties to get around more easily; and especially to visit Mary who spent long periods in hospital at that time). Whether she actually did find the ten pounds, or whether she withdrew it from her sparse bank account in order to justify giving us some special gift is something I have often thought about.

If mum had some unusual ways, she also knew how to encourage me to write. While she doubted with great fervour that I would be able to do something worth while on the wireless, she had a picture in her mind of me as a writer (part time of course - the bank had top priority) and allowed me space at the end of the kitchen table. There I placed my writing pads, exercise books and other aids to the creative process, and there I slaved each evening, after homework, on the latest piece for Sunbeams - with half an ear on the Lux Radio Theatre booming out from the dining room.

I tried my hand at writing scripts for some of the shows I heard on the air. There was one program, late night for me around 9 o'clock, called "Melody Riddles". Harry Dearth, who produced the Lux Radio Theatre, handled this program (I suspect under protest). Listeners were asked to submit brief comedy scripts, in which the name of a popular song was hidden in the dialogue:-

Voice 1: We must get in touch with the old folks ...

Voice 2: At home we used to call them elderly people..

Presto! You've carefully hidden the name of a great tune of the times - "The Old Folks at Home". Clever,eh?

This was a challenge. And each week at least one of my scripts would end up on the desk of the producer in Sydney, but got no further. I never did collect a prize. It was worth as much as two good Sunbeams stories - one guinea. Forgive me if I believe that most of the scripts were written in the home of the producer or one of his minions, the way most of us suspect some Letters to the Editor are created today.

I began to write other things, too. As time went on I managed to get quite a few printed in the two Sydney afternoon newspapers - mainly in the Daily Mirror as it was then, and indeed that became a regular source of pocket money especially when I made my way into Sydney broadcasting in 1949.

But before that, there was a big event for me as my schooldays continued.

Over on a hill not far from our home (probably two or three miles away by road) a tower was being built. I was convinced it was a broadcasting tower, because I'd seen a picture of the tower of the new Sydney station, 2SM, in the authoritative publication "Wireless Weekly".

I turned out to be correct, but it took some time to prove it. There were two towers eventually, and that sorted it out for me. Then my grandfather came for a visit. As a surveyor, his interest was in finding out how high they were compared to the surrounding areas. I don't know why, and maybe he didn't either. Perhaps he was just catering to the interest of his only (at that time) grandson.

We took a walk out and asked one of the men working there what it was all about.

"It's for 2KA", he told us.

Mum was with us, and she probably felt bad about the discussion. To start with, she didn't like 2KA. It had been transmitting from further up the mountains for a couple of years, and she had become firmly convinced that one of the announcers had been talking to her one day when she heard him say. "Hope you got home OK on that bicycle, mum".

Why she tuned in at that time to hear this message was something that worried me somewhat, for 2KA was the pits. 2UE and 2KY were simply "common", but 2KA defied polite description.

I was determined that I would get to know someone at 2KA so they could tell me how I could get me a job on the wireless. After all, I had already told my school mates that was what I was going to do when I grew up, and here I was at high school and the only prospect of employment looked like being in a bank.

It was up to me to do something about it.

Meantime, there was a school holiday coming up, and I knew there was a casual job available as a telegram messenger boy. All you needed was a bicycle, and that was something I had.

It was a good job. Not as profitable as Sunbeams, where the going rate was 10/6 for a story that took half an hour to write, but steady at 10/- for about 48 hours each week.

The other messenger was Laurie. We divided the town into two halves - he took the side he lived in. 2KA was in his territory.

I had been outsmarted. I tried to negotiate with Laurie, using the undeniable fact that most of the People on my side seemed to have ice chests stacked with soft drinks, and their largesse was legendary. He countered by stressing that the cake shop was in his territory, and the owner was generous to a fault.

Checkmate!

Yet, out of all of this came what was a big event for me.

Laurie delivered a telegram to the transmitting station, was invited inside to take a look at it, and told the engineer about me and my plans to work in radio. He came back with the message that I was to drop in any afternoon the following week. (Had I been able to find him when I became Sales manager at 2UE, I would have offered him a job: his sales skill would have made him a natural).

Of course, I was immediately ready to take on the world. Here was my chance. I would soon be challenging Jack Davey (this top man was in uniform, entertaining American and Australian troops, so the opportunity was certainly there). I would be an overnight sensation - nothing could stop me.

There would be quiz shows, and top line variety shows, like the one Wilfred Thomas compered on the ABC each week, with a full orchestra (I didn't realise how apt that description was), and of course, there would be the fans and the pictures in "Wireless Weekly" and "Radio Pictorial". I would be reading the news, playing the latest records, appearing in radio plays...

The bank would have to wait. Forever, with any luck.

I didn't sleep much for the seven days before I got to 2KA, and on the day, I had to pretend that I was ill late in the afternoon, so I could get off work early and arrive at the station before sundown.

My writing stopped. Not even a "Melody Riddles" script.

Small wonder that the first visit started as a bit of a let-down.

Now for stories, I thought.

I had received book of short stories at the primary school as a prize the year I left - 1938. I picked it up again - and I was suddenly lifted into a new world - mainly the incredible world of Steven Leacock, whose "Soaked in Seaweed" I could once recite almost in its entirety from memory.

This, I thought, was the kind of stuff I would like to write. It was just good fun. I had a go. I wrote three hundred words of nonsense.

Three weeks later, it was published. Not only that, but it was in the prime position where the prize was 10/6, the same price as the Mad Hatter's Hat in Alice in Wonderland..

Sure, Cousin Marie had changed the title, cut it down to Sunbeams size, and she'd changed the last line (the original probably being very much a school yard idea of humour, but I liked it better). No matter. It was there. It had my name on it, although I now wrote under the name Thomas, rather than Tom. I had decided that Thomas looked better for a writer.

There followed several of these, all credited to me and each one showing a slightly different address. The name of the house seemed to change with each publication. Did we move from house to house in Wood Street? Hardly possible. There was only one house there. This cries out for an explanation.

The reason was simple. My mother had become sick and tired of being poor. She had taken up the sciences of astrology and numerology and with her usual enthusiasm for a project, had put what little knowledge she gained into determined full-time practice.

It was my fault, of course. In 1936 or thereabouts, someone had handed me a copy of the Aspro Year Book on the way home from school. This eminent publication, now sadly gone, was an annual full of information about what the stars said must inevitably happen during the following year, the benefits of numerology, how to plant by the stars, horoscopes of the famous, and a million conflicting slogans for the product it was named for, none of which would get past today's health watchdogs.

First came numerology, where you added up any number that was more than one digit long and kept adding the result together until you got a single number. Then you could tell whether your number was "fortunate". If you wanted to check out your name in numerology, it was also simple: every letter of the alphabet had a number. You added all the numbers up.

Mum changed the name of the house in quick succession from Thornton to Allambie to Alanbie and so many others that sometimes I had to check on the house name, just in case I'd missed something. Each one, of course, was more likely to produce wealth and success and happiness than its predecessor, but always failing in some mysterious way.

Then to the stars. This became a serious business, especially since she could hear at least two experts on the subject on radio. (It was commercial radio, which she had no time for, but at least it was on two of the "better" ones, 2GB and 2UW). 2GB had a gentleman from a library which specialised in Theosophical topics. The Theosophical Society owned the 2GB licence. This library had a stack of books on astrology, many of them written half a century before. The other guru was an Egyptian gentleman who apparently materialised in the 2UW studio in full traditional garb two or three times a week. But it encouraged mum to study the art of telling her future by the stars.

So our trips to Sydney now ended up, not in the studios watching a children's session, but at the Library in the basement of 29 Bligh Street - an address I was to get to know and love many years later. At the time the building also contained 2GB and 2UE.

The way to win the lottery, according to the way my mother read the astrology books, was to buy a ticket at the time when the stars were exactly right. She would look for a propitious sign - like the conjunction of Jupiter and Venus, for example. If it were to occur at 9.37 Australian Eastern Standard Time, she would take the early morning train to Sydney, ride the tram down Castlereagh Street to Barrack Street, then walk up to the Lottery Office. There she would stand on the steps until about fifteen minutes before the appointed time and before joining a queue.

There would be a great deal of shuffling and dodging, as she realised that she would get to the head of the line before the selected time. The strategy then was to turn to the person behind her and offer to change places. This working back process might happen two or three times before she got it just right - even then she lived in dread of the person ahead of her ordering several tickets at the same time to the ruination of her scientific plan..

When she got to the counter, if there were just a few seconds to wait, she would fiddle with the papers until the very instant of the conjunction, and triumphantly purchase her Ticket to Freedom.

Sadly, it never happened. I privately formed the opinion that she was not taking into account the enormous time difference between Earth and Venus.

She would have loved the no-nonsense method of buying a lottery ticket today.

The best thing that ever did occur was when mum spotted a ten pound note in the gutter as she was riding her bike. (She had bought one in her early forties to get around more easily; and especially to visit Mary who spent long periods in hospital at that time). Whether she actually did find the ten pounds, or whether she withdrew it from her sparse bank account in order to justify giving us some special gift is something I have often thought about.

If mum had some unusual ways, she also knew how to encourage me to write. While she doubted with great fervour that I would be able to do something worth while on the wireless, she had a picture in her mind of me as a writer (part time of course - the bank had top priority) and allowed me space at the end of the kitchen table. There I placed my writing pads, exercise books and other aids to the creative process, and there I slaved each evening, after homework, on the latest piece for Sunbeams - with half an ear on the Lux Radio Theatre booming out from the dining room.

I tried my hand at writing scripts for some of the shows I heard on the air. There was one program, late night for me around 9 o'clock, called "Melody Riddles". Harry Dearth, who produced the Lux Radio Theatre, handled this program (I suspect under protest). Listeners were asked to submit brief comedy scripts, in which the name of a popular song was hidden in the dialogue:-

Voice 1: We must get in touch with the old folks ...

Voice 2: At home we used to call them elderly people..

Presto! You've carefully hidden the name of a great tune of the times - "The Old Folks at Home". Clever,eh?

This was a challenge. And each week at least one of my scripts would end up on the desk of the producer in Sydney, but got no further. I never did collect a prize. It was worth as much as two good Sunbeams stories - one guinea. Forgive me if I believe that most of the scripts were written in the home of the producer or one of his minions, the way most of us suspect some Letters to the Editor are created today.

I began to write other things, too. As time went on I managed to get quite a few printed in the two Sydney afternoon newspapers - mainly in the Daily Mirror as it was then, and indeed that became a regular source of pocket money especially when I made my way into Sydney broadcasting in 1949.

But before that, there was a big event for me as my schooldays continued.

Over on a hill not far from our home (probably two or three miles away by road) a tower was being built. I was convinced it was a broadcasting tower, because I'd seen a picture of the tower of the new Sydney station, 2SM, in the authoritative publication "Wireless Weekly".

I turned out to be correct, but it took some time to prove it. There were two towers eventually, and that sorted it out for me. Then my grandfather came for a visit. As a surveyor, his interest was in finding out how high they were compared to the surrounding areas. I don't know why, and maybe he didn't either. Perhaps he was just catering to the interest of his only (at that time) grandson.

We took a walk out and asked one of the men working there what it was all about.

"It's for 2KA", he told us.

Mum was with us, and she probably felt bad about the discussion. To start with, she didn't like 2KA. It had been transmitting from further up the mountains for a couple of years, and she had become firmly convinced that one of the announcers had been talking to her one day when she heard him say. "Hope you got home OK on that bicycle, mum".

Why she tuned in at that time to hear this message was something that worried me somewhat, for 2KA was the pits. 2UE and 2KY were simply "common", but 2KA defied polite description.

I was determined that I would get to know someone at 2KA so they could tell me how I could get me a job on the wireless. After all, I had already told my school mates that was what I was going to do when I grew up, and here I was at high school and the only prospect of employment looked like being in a bank.

It was up to me to do something about it.

Meantime, there was a school holiday coming up, and I knew there was a casual job available as a telegram messenger boy. All you needed was a bicycle, and that was something I had.

It was a good job. Not as profitable as Sunbeams, where the going rate was 10/6 for a story that took half an hour to write, but steady at 10/- for about 48 hours each week.

The other messenger was Laurie. We divided the town into two halves - he took the side he lived in. 2KA was in his territory.

I had been outsmarted. I tried to negotiate with Laurie, using the undeniable fact that most of the People on my side seemed to have ice chests stacked with soft drinks, and their largesse was legendary. He countered by stressing that the cake shop was in his territory, and the owner was generous to a fault.

Checkmate!

Yet, out of all of this came what was a big event for me.

Laurie delivered a telegram to the transmitting station, was invited inside to take a look at it, and told the engineer about me and my plans to work in radio. He came back with the message that I was to drop in any afternoon the following week. (Had I been able to find him when I became Sales manager at 2UE, I would have offered him a job: his sales skill would have made him a natural).

Of course, I was immediately ready to take on the world. Here was my chance. I would soon be challenging Jack Davey (this top man was in uniform, entertaining American and Australian troops, so the opportunity was certainly there). I would be an overnight sensation - nothing could stop me.

There would be quiz shows, and top line variety shows, like the one Wilfred Thomas compered on the ABC each week, with a full orchestra (I didn't realise how apt that description was), and of course, there would be the fans and the pictures in "Wireless Weekly" and "Radio Pictorial". I would be reading the news, playing the latest records, appearing in radio plays...

The bank would have to wait. Forever, with any luck.

I didn't sleep much for the seven days before I got to 2KA, and on the day, I had to pretend that I was ill late in the afternoon, so I could get off work early and arrive at the station before sundown.

My writing stopped. Not even a "Melody Riddles" script.

Small wonder that the first visit started as a bit of a let-down.

Chapter Three

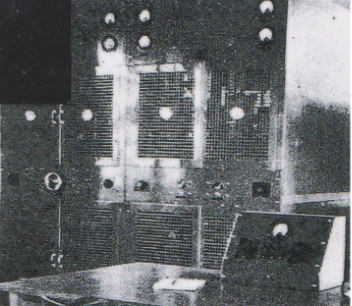

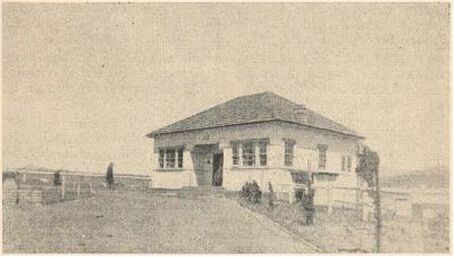

2KA Wentworth Falls - Bruce Carty Collection

2KA Wentworth Falls - Bruce Carty Collection

THE topic was no longer writing . Phil was now talking about the first radio station I ever really knew.

The steps up to the 2KA transmitter were old timber, with a hand rail at one side, and the prospect of those ten or twelve steps staying there much longer were fairly remote. I climbed carefully. After all, if this was to be my entry into the radio industry, I'd better be able to walk around later.

The wind blew up from the valley below, like something only an arctic explorer might have faced. But the view was fantastic - all the way down the mountains to Sydney.

The double doors were locked.

I knocked.

I couldn't help noticing that the doors needed painting. There was a hint of a dull green on them, but whether that was the last coat or the first one was hard to figure. I got the impression that maybe the whole original building had been moved in its entirety form whatever it had been a a wartime economy measure. As I got to know the company better, I knew I'd been right. Economy was the operational system.

There wasn't any answer to my first knock. It may have been a bit timid. After all, this was a big step, and I didn't want to spoil the impression by being too aggressive.

At the second knock the door was opened. A man in overalls, cigarette in a long holder, peered at me, then opened the door wide, and with a sweep of his arm, beckoned me inside.

It was almost as cold inside as it had been outside, the single-bar radiator making absolutely no contribution to the climate.

The steps up to the 2KA transmitter were old timber, with a hand rail at one side, and the prospect of those ten or twelve steps staying there much longer were fairly remote. I climbed carefully. After all, if this was to be my entry into the radio industry, I'd better be able to walk around later.

The wind blew up from the valley below, like something only an arctic explorer might have faced. But the view was fantastic - all the way down the mountains to Sydney.

The double doors were locked.

I knocked.

I couldn't help noticing that the doors needed painting. There was a hint of a dull green on them, but whether that was the last coat or the first one was hard to figure. I got the impression that maybe the whole original building had been moved in its entirety form whatever it had been a a wartime economy measure. As I got to know the company better, I knew I'd been right. Economy was the operational system.

There wasn't any answer to my first knock. It may have been a bit timid. After all, this was a big step, and I didn't want to spoil the impression by being too aggressive.

At the second knock the door was opened. A man in overalls, cigarette in a long holder, peered at me, then opened the door wide, and with a sweep of his arm, beckoned me inside.

It was almost as cold inside as it had been outside, the single-bar radiator making absolutely no contribution to the climate.

2KA Wentworth Falls Studio

- Bruce Carty Collection

2KA Wentworth Falls Studio

- Bruce Carty Collection

Inside, there was a vast area with almost nothing in it. No floor covering except in one or two places where someone had thrown a rug down. There were too big machines standing like the sphinx in my home copy of Lands and People, and there was a pervading buzzing sound. In the centre of the room, sitting alone next to a roof support, was a small desk containing a telephone and a mysterious combination of a dial and two knobs. To my right, looking out through the widow that faced the Great Western Highway, was another desk. This one was much larger, and it had two turntables, a microphone, and a set of knobs and dials. That, I decided immediately, was the studio, even though the whole set up was simply in a corner of the transmitter building. Normally, you'd think, a studio ought to at least have four walls around it.

It didn't look like much of a place - it had absolutely no glamour about it. What had I come to?

I turned to the man who'd opened the door, who was watching my appraisal of the place with a smile. He put out his hand.

"I'm Tom Toakley", he said, "and you'll be Tom".

We got along fine from the moment I realised he was going to let me play with the

studio controls.

He explained that the station was off the air in the afternoons until 5 o'clock, and which time it started up again with a program coming from "our Sydney studio". I quickly discovered that the Sydney studio did not belong to 2KA, although they had had one in the past. The Sydney studio belonged to 2GZ, whose transmitter was at Orange in the centre of New South Wales.

The Sydney location allowed 2GZ to get a share of the lucrative commercial recording business.

Because of wartime measures, and because 2KA could not support itself with advertising, a partnership had been struck between the owners of the two stations to share programs - 2KA contributed very little at all.

At that time, I wasn't conscious that this was a fascinating arrangement. 2KA was owned by former Labor Premier and enemy of the free enterprise stalwarts Mr Jack Lang, and 2GZ was owned by the Grazier's Association - about as Country Party as you could get.

"I'll show you how you work the panel," said my new friend, "and you can play around with it for a bit".

It was exciting! My hands trembled as I tried to put a needle into the pick-up head. I learned that these pickups were different from the one on the gramophone at home. There were certain kinds of needles to be used. You had to know which of three or four kinds was appropriate - it depended on the kind of disc you were about to play. And each needle was to be used for one play only.

There were "trailers", used with acetate recordings, acetate being a soft material used in radio production studios to do a quick copy of a commercial. There were green shanks and red shanks for hardier records, and plain old steel needles for the old 78rpm records.

Pick-up needles had to be screwed in and tested to see that they were firmly in place. This was done by putting your index finger on the point of the needle and trying to

move it, a process damaging to one's fingerprints (but only on the index finger). In fact, they did say you could identify a wireless worker by the needle stabs on his or her index finger. I never conducted any research on this.

After three quarters of an hour I was playing records to the satisfaction of Mr.Toakley, but it was time to stop. In fifteen minutes, he told me, the station would start transmitting again. And before that, it was necessary to run a "test" record to see that the transmitter was functioning correctly.

Years later I divined that the test record served only one important purpose - to give the engineers the chance to speak on the air.

The procedure was this:

At about fifteen minutes before resuming transmission, the transmitter had to be brought up to speed. It had been sitting there warming up when I arrived - hence the buzzing sound. Now the high tension had to be switched in. So far so good.

Right on the tick of a quarter to five, Tom Toakley would move to the studio desk, select a brass band record, and having set it up (with new needle in the pickup) switch on the microphone and intone the words "2KA testing". As the music swelled out into the stratosphere, he would check that the "levels" were right (that is, that the sound was not causing the meter to read in the high "red" area), pick up his log book, and note the readings of all the dials on the transmitter.

He was most precise in this matter, and the fact was that he would have had a heart attack if they had not been spot on, for he took great pride in having his transmitters in tip top condition.

Then, as the music was ending, he'd make a gallop to the studio desk, and announce "2KA test concluded. Our program will start five minutes from now..."

I spent many afternoons with him, practicing what had to be done, and listening to his tall stories about the people he knew in the radio business. I was wide-eyed as he spoke about the young actor who filled in as an announcer in Sydney, got himself a revolver and "shot up" the studio one night. And the other announcer who would dash out of the studio while a recorded program was playing and go to the recording studio down the street to earn himself a few extra shillings recording commercials. All went well except for the last time, when he forgot to go back to the station.

It was a wonder he persevered with me, because I must have become something of a nuisance to him. Every afternoon possible, I turned up at the transmitter armed with a hundred questions about why things were done the way they were, and taking over the controls of the studio in a very possessive way.

I noticed that during the afternoon, while the station was off the air, the telephone would ring and Tom would put on a set of headphones and sit quietly at his small desk listening intently.

After some time, perhaps he had yet to learn to trust me, he told me that he was listening to conversations between the manager in Sydney and the manager in Orange. They were brothers and they would discuss plans for programs, new staff, and the financial situation. Tom would not talk about what he learned, but often he would have a quiet smile playing around his lips.

He broke his silence one afternoon, however. He suddenly raised his hands in the air for a moment, then motioned me to be quiet, and held the headphones close to his ears with both hands so as not to miss a word.

He came over to me when the conversation had ended and said:

"They're going to advertise for an announcer in tomorrow's Herald. I think you're ready to apply for it. It's a job in Orange, but they're going to put the new man to work in Sydney for the first couple of weeks. Now here's what you do..."

We planned the letter in minute detail, including a casual mention that I knew Mr Toakley and felt an audition could be arranged from the 2KA transmitter, if that would be satisfactory.

It was wartime and I had a distinct advantage. All the able-bodied people were in the services - all that were left were school kids and old-age pensioners. And I had just left High School with my Intermediate Certificate, with two "A" passes - one in English, and the other, usefully, and incredibly, in woodwork.

It was almost time for the test record, and time for me to go home, draft my letter, return to the post office and send it on its way that very night.

Tom looked at me. "You'd better do the test announcement today", he said. "That'll be practice for you".

I was terrified and excited. Do the test record? Speak into the microphone so people could hear me?

No, I couldn't. Yes, I probably could. All right - are you sure?

My first words on radio are therefore indelibly imprinted on my mind.

At approximately fifteen minutes to five on that chilly winter afternoon, I spoke the immortal words "2KA testing". I put the test record to air all by myself. And three minutes later I reprised with the words "2KA test concluded. Our program will start in five minutes from now".

I didn't have my bicycle with me that day. Probably just as well. I could have had an accident.

Instead of riding, I flew home several feet above the ground, imagining that everyone I passed had heard my announcement. But nobody mentioned it - they must have missed the Big Broadcast.

When I arrived home, I found that nobody there had heard it either.

I realised that other earth-shaking events in my career would probably be similarly ignored. And that was something I was going to have to live with.

It didn't look like much of a place - it had absolutely no glamour about it. What had I come to?

I turned to the man who'd opened the door, who was watching my appraisal of the place with a smile. He put out his hand.

"I'm Tom Toakley", he said, "and you'll be Tom".

We got along fine from the moment I realised he was going to let me play with the

studio controls.

He explained that the station was off the air in the afternoons until 5 o'clock, and which time it started up again with a program coming from "our Sydney studio". I quickly discovered that the Sydney studio did not belong to 2KA, although they had had one in the past. The Sydney studio belonged to 2GZ, whose transmitter was at Orange in the centre of New South Wales.

The Sydney location allowed 2GZ to get a share of the lucrative commercial recording business.

Because of wartime measures, and because 2KA could not support itself with advertising, a partnership had been struck between the owners of the two stations to share programs - 2KA contributed very little at all.

At that time, I wasn't conscious that this was a fascinating arrangement. 2KA was owned by former Labor Premier and enemy of the free enterprise stalwarts Mr Jack Lang, and 2GZ was owned by the Grazier's Association - about as Country Party as you could get.

"I'll show you how you work the panel," said my new friend, "and you can play around with it for a bit".

It was exciting! My hands trembled as I tried to put a needle into the pick-up head. I learned that these pickups were different from the one on the gramophone at home. There were certain kinds of needles to be used. You had to know which of three or four kinds was appropriate - it depended on the kind of disc you were about to play. And each needle was to be used for one play only.

There were "trailers", used with acetate recordings, acetate being a soft material used in radio production studios to do a quick copy of a commercial. There were green shanks and red shanks for hardier records, and plain old steel needles for the old 78rpm records.

Pick-up needles had to be screwed in and tested to see that they were firmly in place. This was done by putting your index finger on the point of the needle and trying to

move it, a process damaging to one's fingerprints (but only on the index finger). In fact, they did say you could identify a wireless worker by the needle stabs on his or her index finger. I never conducted any research on this.

After three quarters of an hour I was playing records to the satisfaction of Mr.Toakley, but it was time to stop. In fifteen minutes, he told me, the station would start transmitting again. And before that, it was necessary to run a "test" record to see that the transmitter was functioning correctly.

Years later I divined that the test record served only one important purpose - to give the engineers the chance to speak on the air.

The procedure was this:

At about fifteen minutes before resuming transmission, the transmitter had to be brought up to speed. It had been sitting there warming up when I arrived - hence the buzzing sound. Now the high tension had to be switched in. So far so good.

Right on the tick of a quarter to five, Tom Toakley would move to the studio desk, select a brass band record, and having set it up (with new needle in the pickup) switch on the microphone and intone the words "2KA testing". As the music swelled out into the stratosphere, he would check that the "levels" were right (that is, that the sound was not causing the meter to read in the high "red" area), pick up his log book, and note the readings of all the dials on the transmitter.

He was most precise in this matter, and the fact was that he would have had a heart attack if they had not been spot on, for he took great pride in having his transmitters in tip top condition.

Then, as the music was ending, he'd make a gallop to the studio desk, and announce "2KA test concluded. Our program will start five minutes from now..."

I spent many afternoons with him, practicing what had to be done, and listening to his tall stories about the people he knew in the radio business. I was wide-eyed as he spoke about the young actor who filled in as an announcer in Sydney, got himself a revolver and "shot up" the studio one night. And the other announcer who would dash out of the studio while a recorded program was playing and go to the recording studio down the street to earn himself a few extra shillings recording commercials. All went well except for the last time, when he forgot to go back to the station.

It was a wonder he persevered with me, because I must have become something of a nuisance to him. Every afternoon possible, I turned up at the transmitter armed with a hundred questions about why things were done the way they were, and taking over the controls of the studio in a very possessive way.

I noticed that during the afternoon, while the station was off the air, the telephone would ring and Tom would put on a set of headphones and sit quietly at his small desk listening intently.

After some time, perhaps he had yet to learn to trust me, he told me that he was listening to conversations between the manager in Sydney and the manager in Orange. They were brothers and they would discuss plans for programs, new staff, and the financial situation. Tom would not talk about what he learned, but often he would have a quiet smile playing around his lips.

He broke his silence one afternoon, however. He suddenly raised his hands in the air for a moment, then motioned me to be quiet, and held the headphones close to his ears with both hands so as not to miss a word.

He came over to me when the conversation had ended and said:

"They're going to advertise for an announcer in tomorrow's Herald. I think you're ready to apply for it. It's a job in Orange, but they're going to put the new man to work in Sydney for the first couple of weeks. Now here's what you do..."

We planned the letter in minute detail, including a casual mention that I knew Mr Toakley and felt an audition could be arranged from the 2KA transmitter, if that would be satisfactory.

It was wartime and I had a distinct advantage. All the able-bodied people were in the services - all that were left were school kids and old-age pensioners. And I had just left High School with my Intermediate Certificate, with two "A" passes - one in English, and the other, usefully, and incredibly, in woodwork.

It was almost time for the test record, and time for me to go home, draft my letter, return to the post office and send it on its way that very night.

Tom looked at me. "You'd better do the test announcement today", he said. "That'll be practice for you".

I was terrified and excited. Do the test record? Speak into the microphone so people could hear me?

No, I couldn't. Yes, I probably could. All right - are you sure?

My first words on radio are therefore indelibly imprinted on my mind.

At approximately fifteen minutes to five on that chilly winter afternoon, I spoke the immortal words "2KA testing". I put the test record to air all by myself. And three minutes later I reprised with the words "2KA test concluded. Our program will start in five minutes from now".

I didn't have my bicycle with me that day. Probably just as well. I could have had an accident.

Instead of riding, I flew home several feet above the ground, imagining that everyone I passed had heard my announcement. But nobody mentioned it - they must have missed the Big Broadcast.

When I arrived home, I found that nobody there had heard it either.

I realised that other earth-shaking events in my career would probably be similarly ignored. And that was something I was going to have to live with.

Chapter Four

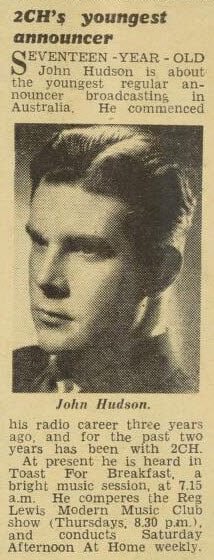

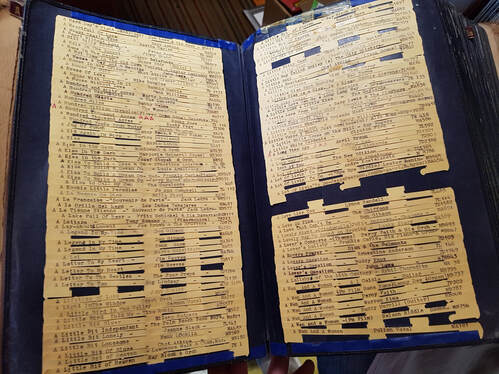

Wireless Weekly March 1935

Wireless Weekly March 1935

arrived in Sydney forty seven years before that audience heard that "you never forget your first job".

The day I heard that the job was mine I went into uncontrolled orbit. If that is a slight exaggeration, then it's certainly true that I tried to send the family cat into orbit (and failed) much to the cat's obvious annoyance. I tossed the poor animal high in the air out of sheer excitement - and although I caught it on the way down, it never trusted me again.

Sixteen and, as one of my family puts it, "proud of it", I was about to start my first job in radio, and I was going to Sydney to find out what it was all about.

It wasn't likely that my mother would let me loose in Sydney, sedately safe as it was in 1942. Nor did she even think about me commuting on a daily basis. I had to stay with my two maiden aunts in Bellevue Hill. They lived in a small mansion in the Federation style, dominated by two monstrously large paintings on the sitting room wall - one my great great grandfather (who chose to die on Christmas Day in 1849) and another of a woman of great character if little beauty, about whom I was not so sure, and whose death, while likely, did not seem to have been recorded.

Allowing me to stay with the Aunts was a major concession, for mum had not willingly spoken to either of them in many years. She was convinced that, given half a chance, they would take her two children and put them in boarding school. I am not sure that they had shown much inclination to do so, nor am I sure that it would have been a bad thing - except that she would have been pretty lonely between school holidays.

Mum's kin, the Rankens, were an old family from the Ayr district in Scotland, some members of which had arrived in Australia (without the assistance of the British Government) around 1810 and settled "on the land". Our branch of the family did not go into sheep raising. Our grandfather was a Government Surveyor who lived and worked for many years in Lismore and then in Dubbo NSW before retiring to Bellevue Hill. There he set to work on two books - one a volume of poems he had written during his working life, and another in which he traced the history of land development in this country - with the warning that the Asian hordes would soon invade and take us over. Its title was "Fire Over Australia" and was published shortly before his death just after the second world war broke out. Unfortunately there were many copies remaining in his estate when he died.

He had also earlier written a book on an aspect of mathematics which, according to family legend, earned him a Fellowship of the Royal Society in London.

He worried a lot about what was then thought of as the "yellow peril" and was proved right very soon after when World War 2 broke out. In a family in which there was a significant degree of odd thinking, he represented the fountain of sanity. Even if he did not think much of the Aeroplane Jelly song.

Proud of the tradition behind the name, one of the Aunts did not really feel comfortable with people of lower standing. Once she remarked to Mary - after someone had said good afternoon to the Aunt and she had walked haughtily onwards, ignoring the impertinence - "Don't they know we're Rankens?"

But I digress.

The Bellevue Hill wireless (and it was called a wireless, not a radio) was only switched on to hear the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, which did not perform all that often. Therefore it was excusable that the two old ladies had not noticed that there was something wrong with the receiver.

You could get 2FC all right. 2FC was one of the two very strong ABC stations, so you might expect to receive it fairly well, but anything else was scratchy.

Both aunts worked in banking, and had done so since the days of the first world war, so when I arrived on the first day, they were safely enscounced in their teller's cages in the city. I let myself in and started to tune in my favourite station.

2KA was faint and totally unintelligible. The thousand watts transmitted from 60 miles distant Wentworth Falls did not survive the atmospherics of the city, thus improving the program enormously.