50 GOLDEN YEARS of BROADCASTING

The Amateur Contribution - By G. Maxwell Hull (VK3ZS)

This 1972 W.I.A. article celebrates the 50th year since formulating the first regulations governing broadcasting back in 1922, following the insistence of the broadcasting companies, the retail and wholesale traders, and the W.I.A. Without such regulatory control, chaos was reigning with both commercial and amateur experimenters transmitting at any old time and anywhere on the available wavelengths. Without regulatory control, the envisaged advantages to peoples all over the world would have been useless. Amateur experimenters were the only people who understood the ‘secrets’ of wireless, and they were composed of professional engineers, chemists, accountants, manufacturers, salesmen, draughtsmen – in fact, from every walk of life came those who participated in this new found science. The electrical and mechanical engineers perhaps had the advantage of greater insight over some of those from other professions; nevertheless, hundreds of people entered the fascinating field of wireless. The W.I.A. is proud of its association with all people who played such an historic part in what can only be described as one of the greatest achievements of mankind. It is certain the broadcast industry has benefited from the dedication of those amateur transmitting licensees it employs.

Great advances had been made in ‘wireless’ technology during WWI to the advantage of the Navy, Army, and the Australian Flying Corps. The wireless experimenters who went to war, and those who stayed at home, were anxious to recommence where they left off in 1914, but the possibility looked forlorn. The authority to control radio was given to the Australian Navy Radio Commander. His first work was that of organising the Commonwealth Radio Service on naval lines and under naval discipline. In 1920 only 21 land stations existed and they were under the control of the Government; there were no private land stations or experimental stations. There were a number of ship stations on Government vessels as well as on vessels privately owned. In the same year, the Radio Commander issued temporary permits to use Wireless Telegraphy apparatus for the purpose of receiving wireless telegraphy signals. The permits were issued pending legislation on the issue of licences to amateurs to conduct experiments in transmitting.

This was a bitter pill to the many anxious experimenters who, before the outbreak of war in 1914, had licences granted to them by the P.M.G. to conduct experimental transmissions. With typical aptitude, they experimented with receiving equipment, organising themselves into clubs (including W.I.A. Divisions) and using every avenue to gain permits for transmitting. Although by 1922 several licences to transmit had been issued, it was not until July of that year that amateur experimenters were granted general licences. With a joint move by the W.I.A. and commercial interests, the Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, was persuaded to act in the interests of promoting the tremendous advantages seen in the newly developed science of wireless, experimental facilities for which had been available to overseas experimenters for some time. The “Wireless Weekly” number 1, (4-8-1922), carried the good news stating the Prime Minister had said that facilities granted in other parts of the world would be given to amateurs here under proper control. No restrictions except those to prevent interference would be imposed. One can imagine bells being rung on that occasion.

The first broadcast transmitting licence was granted in 1922 to Charles MacLurcan of Strathfield; an engineer of some renown (as were many of the early experimenters). Charles MacLurcan was one of the first to transmit music and live programs in Sydney from 1921 on a wavelength of 1400 metres. With the announcement of a general licence by the Prime Minister Hughes, there followed tremendous activity. Experimenters everywhere took out licences, including commercial interests, and, as far as the general public were concerned, broadcasting was born. The experienced engineering amateur soon demonstrated his ability in the newly developing field of wireless. His transmissions were logged and reported by the listening enthusiasts. His experiments included the playing of gramophone records, and, on occasions, live artists. He tried various kinds of aerial systems and read avidly of his transmission reports to assess the coverage. He also developed useful forms of microphone designs to improve the quality of his transmissions.

By 1923 there were severe interference problems between transmissions on similar and adjacent wavelengths, and complaints of amateur transmissions interfering with commercial operations. By pressure from public organisations, and those representing the trade, and professional and amateur licensees, statutory regulations governing broadcasting were drawn up by the Postmaster-General’s department, having taken over again from the Naval department, and these became law on the 1st August 1923. The “definite rules of the road for using the common highway, and some authority to see that the rules were observed”, had come into being; (the wise words of Ernest Fisk in 1919).

The public and commercial enterprises looked to the amateur experimenters for advice and guidance because they were the only people who understood wireless. Almost every publication dealing with the subject was written or edited by amateur experimenters (excluding engineering text books) and many of these in magazine form were, at times, the official organ of the W.I.A., which was the largest of the many representative associations. The amateur experimenter had trodden a hard road to reach the position of public acceptance achieved by 1924, and were most definitely a vital part in the early progress of the broadcast industry. Through the years from 1924 to 1929 he was in everything to do with wireless. Every newspaper and periodical wrote about the amateur experimenters and their achievements. He was employed by commercial stations (and later by the Government owned A.B.C.) and experimented with his own wireless station at home in his spare time. He went into manufacture; producing many component parts, speakers, and wireless receivers of improved standards. He even designed, built, and installed many of the first broadcasting stations.

The W.I.A. organised the first Wireless and Electrical Exhibition at the Melbourne Town Hall in 1924. They also organised a huge exhibition in the Sydney Town Hall in 1925. These exhibitions received the support of most of the commercial manufacturers of wireless reception. Thousands were fascinated by the numerous demonstrations of live broadcast receptions from both commercial and amateur stations situated remote from the exhibition sites; the ability of some receivers to ‘give good loudspeaker strength’ of signals from other States instead of having to use headphones; and the ‘high fidelity’ of one transmission compared with another.

These were the golden days of broadcasting. The country was crazy with ‘wirelessmania’. It had captured the minds of the populace to the point where unskilled people of all ages would have a go at building a crystal receiver to attempt to listen-in to broadcasts. It rapidly reached the stage in 1925 where there were thousands of listeners-in who had paid high prices for their receivers, and the reception of programs was now a part of living. The listeners became critical of transmission quality when sometimes it was the fault of a poor receiver. They criticised the lack of live artists and the ‘canned music’ they had to suffer. By 1926 a Listeners League was formed, claiming that if you owned a receiver, you owned part of the ether and were a shareholder in one of the greatest enterprises of the times. The League’s objectives were for better programs by greater co-operation between listeners and broadcasters.

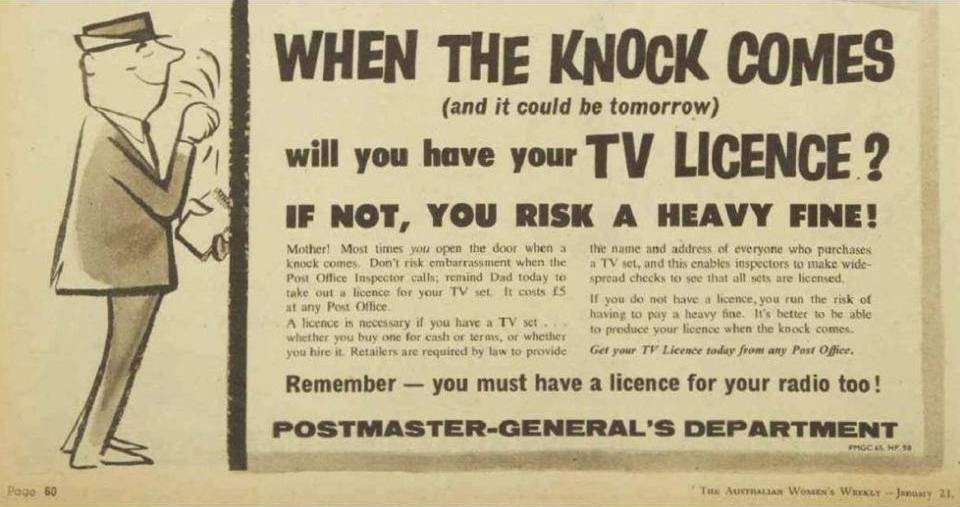

These were perhaps the problem years. References were made to the poor quality of receivers. Many listeners wrongly blamed the broadcasters for the quality of their reception. Aerials had been erected by amateurs (this time the literal meaning) and insurance companies in Victoria set a standard for the safe erection and installation of this part of listeners receiving apparatus. The broadcast stations also had financial problems. In 1925 the listener licence fee was 35/- ($3.50) and the broadcast station relied on part of this for its finance. Many people purchased receivers but didn’t pay the licence fee; hence the stations were not receiving the finance required to improve their programs as demanded by the public. However, the general standard was slowly improving. Engineers were devising new ideas, and new useful products were appearing on the market. New techniques had been developed overseas, and system engineers were able to travel overseas, and return with new ideas for their station. By 1932 many changes had taken place. Modern transmitters using the latest techniques were being built. Amateur experimenters had kept up with modern trends, and were sometimes ahead of the commercial broadcasters, often being praised in the press for the superior quality of their transmissions.

There were many notable contributions by amateurs to broadcasting, including the Holst brothers. Their station, 3BY, transmitted a very high quality signal. They designed and rebuilt 3DB in 1929, which for many years was reported as the station with the highest modulation quality anywhere in Australia. They were exceptionally fine engineers, being the manufacturers of transmitting and audio equipment which was highly respected by the industry. The Listeners League suggested that amateur experimenters should make representations to the Government for encouragement with their experiments, because in the League’s opinion, the broadcasting stations had improved because of the work of distinguished amateurs. The meeting was reminded that the quality of transmission from the high class amateur stations was of a considerably better performance than from many of the “A” class stations.

However, amateur stations were in peril of being closed because the Government was due to take over these bands. The W.I.A. had established itself as the governing body of Australian amateurs, having encouraged most clubs to affiliate with it in order to speak with one voice. Therefore, the W.I.A. was successful in getting the Government to agree to amateurs continuing to broadcast on Sunday mornings before “A” and “B” class stations came on the air, and after about 10 PM when the “A” and “B” class stations had closed. Thousands of people will remember the very excellent programs transmitted by some of these amateur broadcasters.

In 1939, with the outbreak of WWII, all amateur stations were ordered closed for reasons of military security. Following the resumption of amateur transmitting stations in 1947, applications for broadcast band permits were refused. The reason was the Government was faced with applications for commercial licences from hundreds of private companies. With the knowledge and expertise which amateur experimenters gave the broadcasting industry, it survived the many problems of its infancy, and went on to develop from 13 licensed stations in 1925 (not including broadcasting amateurs) to some networks in excess of 181 stations in 1972.

1930 saw the depression years when the industry went through difficult financial times. Engineers worked long hours with less pay. However, there had been interesting technical advances. The electric pickup had been developed in the late 1920s, and this dramatically changed music broadcasts, compared with the old method of placing a microphone in front of a gramophone horn. A.W.A. had commenced making quality transmitting valves which were essential when WWII started, as replacement parts were difficult to obtain due to defence requirements. These days, transcription discs rotated at 33 r.p.m. and standard discs at 78 r.p.m. Record needles were scarce so stations had to re-sharpen them or use cactus needles. Then came wire recorders, which revolutionised broadcasting as dramatically as the electric pickup had done. Then tape recorders and stereo records, with higher quality sound.

Many of the early engineers, including amateur broadcasters, have passed on or retired, but can vividly recall their experiences in broadcasting development. A few broadcasting amateurs are still the Chief Engineers of the modern station where only memories remain of the early broadcasting days. The broadcasting industry is certain to enjoy another 50 Golden Years, but will it be the same as the first 50? Transmitters are now using very reliable components, with equipment remotely controlled. The studio equipment is now mostly solid state. The industry today has to bear the fierce competition of television and other entertainment media. That it will survive and continue to flourish, there seems no doubt. Whilst the Government continues to encourage amateur radio, there is also no doubt that the technological ability of many licensed amateur transmitters will continue to be of benefit to the broadcasting industry.

The W.I.A. wishes the broadcasting industry the continued success it has earned, for it has indeed been a magnificent ‘50 Golden Years of Broadcasting’.

**************************************************************************************************************************************

Great advances had been made in ‘wireless’ technology during WWI to the advantage of the Navy, Army, and the Australian Flying Corps. The wireless experimenters who went to war, and those who stayed at home, were anxious to recommence where they left off in 1914, but the possibility looked forlorn. The authority to control radio was given to the Australian Navy Radio Commander. His first work was that of organising the Commonwealth Radio Service on naval lines and under naval discipline. In 1920 only 21 land stations existed and they were under the control of the Government; there were no private land stations or experimental stations. There were a number of ship stations on Government vessels as well as on vessels privately owned. In the same year, the Radio Commander issued temporary permits to use Wireless Telegraphy apparatus for the purpose of receiving wireless telegraphy signals. The permits were issued pending legislation on the issue of licences to amateurs to conduct experiments in transmitting.

This was a bitter pill to the many anxious experimenters who, before the outbreak of war in 1914, had licences granted to them by the P.M.G. to conduct experimental transmissions. With typical aptitude, they experimented with receiving equipment, organising themselves into clubs (including W.I.A. Divisions) and using every avenue to gain permits for transmitting. Although by 1922 several licences to transmit had been issued, it was not until July of that year that amateur experimenters were granted general licences. With a joint move by the W.I.A. and commercial interests, the Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, was persuaded to act in the interests of promoting the tremendous advantages seen in the newly developed science of wireless, experimental facilities for which had been available to overseas experimenters for some time. The “Wireless Weekly” number 1, (4-8-1922), carried the good news stating the Prime Minister had said that facilities granted in other parts of the world would be given to amateurs here under proper control. No restrictions except those to prevent interference would be imposed. One can imagine bells being rung on that occasion.

The first broadcast transmitting licence was granted in 1922 to Charles MacLurcan of Strathfield; an engineer of some renown (as were many of the early experimenters). Charles MacLurcan was one of the first to transmit music and live programs in Sydney from 1921 on a wavelength of 1400 metres. With the announcement of a general licence by the Prime Minister Hughes, there followed tremendous activity. Experimenters everywhere took out licences, including commercial interests, and, as far as the general public were concerned, broadcasting was born. The experienced engineering amateur soon demonstrated his ability in the newly developing field of wireless. His transmissions were logged and reported by the listening enthusiasts. His experiments included the playing of gramophone records, and, on occasions, live artists. He tried various kinds of aerial systems and read avidly of his transmission reports to assess the coverage. He also developed useful forms of microphone designs to improve the quality of his transmissions.

By 1923 there were severe interference problems between transmissions on similar and adjacent wavelengths, and complaints of amateur transmissions interfering with commercial operations. By pressure from public organisations, and those representing the trade, and professional and amateur licensees, statutory regulations governing broadcasting were drawn up by the Postmaster-General’s department, having taken over again from the Naval department, and these became law on the 1st August 1923. The “definite rules of the road for using the common highway, and some authority to see that the rules were observed”, had come into being; (the wise words of Ernest Fisk in 1919).

The public and commercial enterprises looked to the amateur experimenters for advice and guidance because they were the only people who understood wireless. Almost every publication dealing with the subject was written or edited by amateur experimenters (excluding engineering text books) and many of these in magazine form were, at times, the official organ of the W.I.A., which was the largest of the many representative associations. The amateur experimenter had trodden a hard road to reach the position of public acceptance achieved by 1924, and were most definitely a vital part in the early progress of the broadcast industry. Through the years from 1924 to 1929 he was in everything to do with wireless. Every newspaper and periodical wrote about the amateur experimenters and their achievements. He was employed by commercial stations (and later by the Government owned A.B.C.) and experimented with his own wireless station at home in his spare time. He went into manufacture; producing many component parts, speakers, and wireless receivers of improved standards. He even designed, built, and installed many of the first broadcasting stations.

The W.I.A. organised the first Wireless and Electrical Exhibition at the Melbourne Town Hall in 1924. They also organised a huge exhibition in the Sydney Town Hall in 1925. These exhibitions received the support of most of the commercial manufacturers of wireless reception. Thousands were fascinated by the numerous demonstrations of live broadcast receptions from both commercial and amateur stations situated remote from the exhibition sites; the ability of some receivers to ‘give good loudspeaker strength’ of signals from other States instead of having to use headphones; and the ‘high fidelity’ of one transmission compared with another.

These were the golden days of broadcasting. The country was crazy with ‘wirelessmania’. It had captured the minds of the populace to the point where unskilled people of all ages would have a go at building a crystal receiver to attempt to listen-in to broadcasts. It rapidly reached the stage in 1925 where there were thousands of listeners-in who had paid high prices for their receivers, and the reception of programs was now a part of living. The listeners became critical of transmission quality when sometimes it was the fault of a poor receiver. They criticised the lack of live artists and the ‘canned music’ they had to suffer. By 1926 a Listeners League was formed, claiming that if you owned a receiver, you owned part of the ether and were a shareholder in one of the greatest enterprises of the times. The League’s objectives were for better programs by greater co-operation between listeners and broadcasters.

These were perhaps the problem years. References were made to the poor quality of receivers. Many listeners wrongly blamed the broadcasters for the quality of their reception. Aerials had been erected by amateurs (this time the literal meaning) and insurance companies in Victoria set a standard for the safe erection and installation of this part of listeners receiving apparatus. The broadcast stations also had financial problems. In 1925 the listener licence fee was 35/- ($3.50) and the broadcast station relied on part of this for its finance. Many people purchased receivers but didn’t pay the licence fee; hence the stations were not receiving the finance required to improve their programs as demanded by the public. However, the general standard was slowly improving. Engineers were devising new ideas, and new useful products were appearing on the market. New techniques had been developed overseas, and system engineers were able to travel overseas, and return with new ideas for their station. By 1932 many changes had taken place. Modern transmitters using the latest techniques were being built. Amateur experimenters had kept up with modern trends, and were sometimes ahead of the commercial broadcasters, often being praised in the press for the superior quality of their transmissions.

There were many notable contributions by amateurs to broadcasting, including the Holst brothers. Their station, 3BY, transmitted a very high quality signal. They designed and rebuilt 3DB in 1929, which for many years was reported as the station with the highest modulation quality anywhere in Australia. They were exceptionally fine engineers, being the manufacturers of transmitting and audio equipment which was highly respected by the industry. The Listeners League suggested that amateur experimenters should make representations to the Government for encouragement with their experiments, because in the League’s opinion, the broadcasting stations had improved because of the work of distinguished amateurs. The meeting was reminded that the quality of transmission from the high class amateur stations was of a considerably better performance than from many of the “A” class stations.

However, amateur stations were in peril of being closed because the Government was due to take over these bands. The W.I.A. had established itself as the governing body of Australian amateurs, having encouraged most clubs to affiliate with it in order to speak with one voice. Therefore, the W.I.A. was successful in getting the Government to agree to amateurs continuing to broadcast on Sunday mornings before “A” and “B” class stations came on the air, and after about 10 PM when the “A” and “B” class stations had closed. Thousands of people will remember the very excellent programs transmitted by some of these amateur broadcasters.

In 1939, with the outbreak of WWII, all amateur stations were ordered closed for reasons of military security. Following the resumption of amateur transmitting stations in 1947, applications for broadcast band permits were refused. The reason was the Government was faced with applications for commercial licences from hundreds of private companies. With the knowledge and expertise which amateur experimenters gave the broadcasting industry, it survived the many problems of its infancy, and went on to develop from 13 licensed stations in 1925 (not including broadcasting amateurs) to some networks in excess of 181 stations in 1972.

1930 saw the depression years when the industry went through difficult financial times. Engineers worked long hours with less pay. However, there had been interesting technical advances. The electric pickup had been developed in the late 1920s, and this dramatically changed music broadcasts, compared with the old method of placing a microphone in front of a gramophone horn. A.W.A. had commenced making quality transmitting valves which were essential when WWII started, as replacement parts were difficult to obtain due to defence requirements. These days, transcription discs rotated at 33 r.p.m. and standard discs at 78 r.p.m. Record needles were scarce so stations had to re-sharpen them or use cactus needles. Then came wire recorders, which revolutionised broadcasting as dramatically as the electric pickup had done. Then tape recorders and stereo records, with higher quality sound.

Many of the early engineers, including amateur broadcasters, have passed on or retired, but can vividly recall their experiences in broadcasting development. A few broadcasting amateurs are still the Chief Engineers of the modern station where only memories remain of the early broadcasting days. The broadcasting industry is certain to enjoy another 50 Golden Years, but will it be the same as the first 50? Transmitters are now using very reliable components, with equipment remotely controlled. The studio equipment is now mostly solid state. The industry today has to bear the fierce competition of television and other entertainment media. That it will survive and continue to flourish, there seems no doubt. Whilst the Government continues to encourage amateur radio, there is also no doubt that the technological ability of many licensed amateur transmitters will continue to be of benefit to the broadcasting industry.

The W.I.A. wishes the broadcasting industry the continued success it has earned, for it has indeed been a magnificent ‘50 Golden Years of Broadcasting’.

**************************************************************************************************************************************